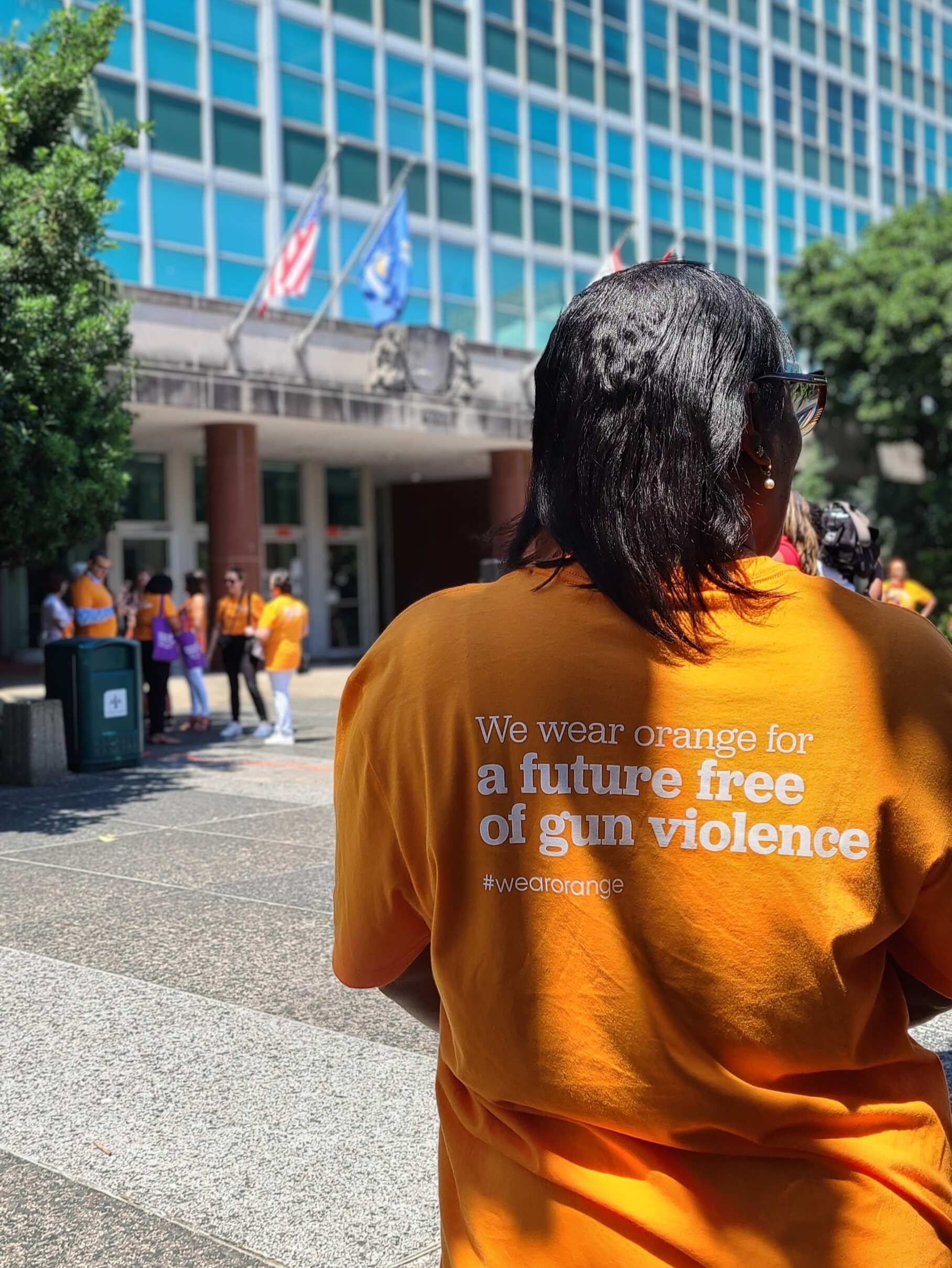

Gun Violence Prevention Resources

Discussing and addressing complex social problems requires a broad understanding of their contributing factors and the consequences of not addressing them. Identified as a major public health risk, gun violence in the United States can impact individuals across their lifespans.

Conversations around its root causes as well as preventative strategies and interventions can mitigate that risk and support safe, thriving communities. The following resources provide information and actionable steps to reducing and preventing gun violence.

Talking Points

- Gun violence is a preventable issue that alters the lives of individuals, families, and communities nationwide. Over half of gun deaths are by suicide, accidental, or involve law enforcement. All of these are avoidable outcomes with increased awareness, training, and use of safe storage.

- Ending gun violence is a public health imperative.

- Nearly 49,000 Americans died in 2021 from gun-related injuries. 81% of homicides and 55% of suicides involve a firearm.

- Louisiana has one of the highest gun death rates in the United States. Gulf Coast states of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama are in the top 5. All three states have gun ownership rates between 48% and 50%, meaning that half of all adults live in a household with a firearm.

- The roots of gun violence are structural, systemic, and linked to decades of oppressive policies like racial segregation (redlining) and divestment and underinvestment in economic and educational opportunity. This means that the solutions must also occur at the community and societal levels.

- Data collection around gun violence must be streamlined and integrated so that it can be evaluated and monitored. Local, state, and federal sources are currently disparate and lack comprehensive demographic information in order to examine trends by location, race, ethnicity, gender, and other socioeconomic factors.

- Funding for gun violence research must increase. Federal research funding on mortality is typically allocated in accordance with the cause of death’s societal burden. That isn’t true for gun violence. For decades, gun lobbyists successfully blocked federal funding for gun violence research, leaving knowledge and understanding far behind that for other causes of death. While this freeze has thawed over the past three years, the federal government spends only $57 on research for every gun death. Increased funding around gun violence could lead to the same significant reduction in deaths that occurred when it increased and maintained funding around motor vehicle safety.

Resources:

VPI's Approach to Violence Prevention

- The Violence Prevention Institute examines the systemic and structural roots of gun violence to support communities, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies implement intervention, prevention, and policy approaches to end gun violence.

- Supported by CDC funding, the VPI’s Center for Youth Equity partners with hospital trauma centers to examine and implement gun violence intervention and prevention approaches.

- The VPI’s Gun Violence Policy Lab performs data analysis on various municipal and state sources to evaluate and monitor trends in gun violence to develop evidence-informed solutions.

- The VPI includes experts across fields, including public health, medicine, social work, psychology, sociology, engineering, and law.

- VPI researchers examine and provide recommendations about the connections between gun violence and possible risk and protective factors related to structural racism, built environment, food insecurity, childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, police encounters, gun-related behaviors and beliefs, and safe storage.

Types of Gun Violence

Conversations around gun violence need to include awareness around its types. Media often focus on mass shootings or community violence, but firearms are also often involved in suicide attempts, intimate partner violence, accidents, and legal intervention.

- Intentionally self-inflicted. This definition includes firearm suicide or nonfatal self-harm injury from a firearm. 54% of all gun deaths are suicides, and 55% of suicides involve a gun.

- Interpersonal violence. This definition includes firearm homicide or nonfatal assault injury from a firearm.

- Homicide – Over 35% of all gun deaths are homicides, and 81% of homicides involve firearms.

- Intimate Partner Violence – IPV victims are five times more likely to be killed when their abuser has access to a gun. 56% of intimate partner homicides involve a firearm.

- Mass shootings – We now define a mass shooting as any incident in which four or more people are shot and wounded or killed, excluding the shooter. Both the number of mass shooting incidents and the number of people shot in them have increased since 2015, reaching a high of 686 mass shooting incidents in 2021.

- Legal intervention. This definition includes firearm injuries inflicted by the police or other law enforcement agents acting in the line of duty. CDC and other government-collected data under-counts police-involved injuries and deaths. The Washington Post’s Fatal Force database, a reputable source which researchers feel adequately reports on police-involved shootings, found that 1,000 Americans are shot and killed by police every year.

- Unintentional. This definition includes fatal or nonfatal firearm injuries that happen while someone is cleaning or playing with a firearm or other incidents of an accidental firing without evidence of intentional harm. About 1% of all gun deaths are unintentional.

Resources:

- https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/firearms/fastfact.html

- https://efsgv.org/learn/type-of-gun-violence/gun-violence-in-the-united…

- https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/04/26/what-the-data-says-a…

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings…;

- https://giffords.org/lawcenter/gun-violence-statistics/

- https://everytownresearch.org/mass-shootings-in-america/

Dispelling Myths about Gun Violence

Is gun violence is a mental health issue?

Yes and no. Research shows that the vast majority of people diagnosed with mental illness are not violent, and that mental illness is not the only predictor of interpersonal violence. In fact, a person with a mental illness is more likely to be a victim than a perpetrator of gun violence, and improved mental health care is a protective factor, especially in the case of suicide. Blaming gun violence on mental illness only continues stigmatization and perpetuates fear, prejudice, and ableism. The roots of gun violence extend beyond an individual’s mental well-being and into the systems and structures that perpetuate gun violence as well as inequality and lack of opportunity. In addition to providing equitable access to mental and behavioral health services, policymakers must remove oppressive barriers and instead promote protective factors that enable individuals, families, and communities to thrive.

Resources:

- https://www.americanprogress.org/article/debunking-myths-the-gun-lobby-…

- https://efsgv.org/learn/learn-more-about-gun-violence/mental-illness-an…

Doesn’t gun violence happen everywhere equally?

No. Globally, the United States has a gun homicide rate that is 26 times higher than that of other developed nations. Nationally, guns are now the leading cause of death among young people under the age of 18. Louisiana has one of the highest gun death rates in the United States, and with other Gulf States of Mississippi and Alabama are among the five highest in the nation. Individually, gun violence disproportionately affects Black Americans as they are 10 times more likely than white Americans to die by gun homicide and 3 times more likely to be fatally shot by police. Recognizing these disparities allows a public health approach to center and partner with communities on prevention and intervention approaches that get to the root of gun violence.

Resources:

- https://www.americanprogress.org/article/debunking-myths-the-gun-lobby-…

- https://www.everytown.org/issues/gun-violence-black-americans/

Will owning a gun improve safety?

No. The evidence base around gun ownership shows that it increases the risk of homicide, suicide, and accidental injury. This is especially true for children and those adults experiencing intimate partner violence and suicidal ideation. Additionally, guns are used more often in homicides than in justifiable acts of self-defense at a ratio of 34:1 and are more likely to be stolen than used for self-defense. Not acknowledging that firearm prevalence in the United States is a contributing factor in gun violence results in misguided and dangerous policies and apathetic attitudes toward safe storage.

Resource: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/myth-vs-fact-debunking-gun-lob…

Evidence-based Gun Violence Prevention

Centering the evidence-base on public health and violence prevention, a combination of community-based approaches, social norm change, policy change, and increased funding can end gun violence.

- Apply a public health approach that defines the issue, identifies risk and protective factors, develops and tests prevention strategies, and ensures widespread adoption of effective strategies.

- Acknowledge address the risk factors associated with racism, poverty, lack of economic opportunity, social mobility, and built environment

- Leverage community and government resources to promote protective factors like

- Positive social orientation

- Developed social competencies

- Connectedness to family and neighborhood

- Involvement in social activities and interests

- Higher quality education

- Increased employment opportunities

- Implement community-based interventions to mitigate risk factors and promote protective factors

- Center and invest in BIPOC-led gun violence prevention organizations

- Support families and schools because positive experiences and environments are protective factors for young people

- Improve equal access to economic opportunity

- Increase access to education and social services

- Enhance mental health access

- Improve the consistency and accessibility of data collection from federal, state, and local government

- Fund research, especially strengths-based studies that understand and can promote protective factors

- Promote safe storage

- Advocate for common sense gun policies and oppose those that make guns more prevalent and accessible

Resources:

- https://www.brookings.edu/essay/addressing-the-root-causes-of-gun-viole…

- https://efsgv.org/learn/type-of-gun-violence/gun-violence-in-the-united…

- https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/firearms/fastfact.html

- https://publichealth.jhu.edu/departments/health-policy-and-management/r…

- https://efsgv.org/wp-content/uploads/EFSGV_REIA_Framework.pdf

- https://efsgv.org/wp-content/uploads/PublicHealthApproachToGVP-EFSGV.pdf

- https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/gun-violence-prevention

- https://www.apha.org/-/media/files/pdf/factsheets/200221_gun_violence_f…

Websites

Websites

Films & Videos

Books

Bullets into Bells: Poets & Citizens Respond to Gun Violence by Brian Clements, Alexandra Teague and Dean Rader

Carry: A Memoir of Survival on Stolen Land Land by Toni Jensen

Glimmer of Hope by The March for Our Lives Founders

Parkland Speaks: Survivors from Marjory Stoneman Douglas Share Their Stories edited by Sarah Lerner

Rest in Power: The Enduring Life of Trayvon Martin by Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin

The Second Amendment: A Biography by Michael Waldman

The Violence Inside Us: A Brief History of an Ongoing American Tragedy by Chris Murphy

Publications from VPI Affiliates

Ali, A., Broome, J., Tatum, D., Fleckman, J., Theall, K., Chaparro, M. P., Duchesne, J., & Taghavi, S. (2022). The Association between Food Insecurity and Gun Violence in a Major Metropolitan City. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery, 10.1097/TA.0000000000003578. Advance online publication.

Theall, K. P., Francois, S., Bell, C. N., Anderson, A., Chae, D., & LaVeist, T. A. (2022). Neighborhood police encounters, health, and violence in a Southern City. Health Affairs, 41(2), 228–236.

Houghton, A., Jackson-Weaver, O., Toraih, E., Burley, N., Byrne, T., McGrew, P., Duchesne, J., Tatum, D., & Taghavi, S. (2021). Firearm homicide mortality is influenced by structural racism in US metropolitan areas. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery, 91(1), 64–71.

Wamser-Nanney, R., Nanney, J. T., & Constans, J. I. (2020). The Gun Behaviors and Beliefs Scale: Development of a new measure of gun behaviors and beliefs. Psychology of Violence, 10(2), 172–181.

Wamser-Nanney, R., Nanney, J. T., & Constans, J. I. (2020). Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and attitudes toward guns. Psychology of Violence.

Wamser-Nanney, R., Nanney, J. T., & Constans, J. I. (2019). PTSD and attitudes toward guns following interpersonal trauma. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(13-14).

Wamser-Nanney, R., Nanney, J. T., Conrad, E., & Constans, J. I. (2019). Childhood trauma exposure and gun violence risk factors among victims of gun violence. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(1), 99–106.

Address

1440 Canal Street, Suite 1510, New Orleans, LA 70112

social media

@tulanevpi